In this age of digital “everything” (or so it seems) libraries remain a public treasure. Here’s a review from the New York Times Book Review last week about a work of fiction set in one of the oldest public libraries in the world.

Book Review | FICTION

Library As Muse

By EDMUND WHITE

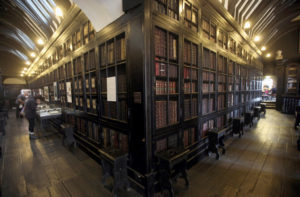

Chetham’s Library in England, one of the world’s oldest public libraries.

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

PUBLIC LIBRARY

And Other Stories

By Ali Smith

220 pp. Anchor Books. Paper, $16.

This collection of stories by one of England’s best novelists is both playful and serious in the manner of Laurence Sterne, the 18th-century author of “Tristram Shandy,” one of the most original novelists of all time, who influenced European literature in a way comparable only to that of the later James Joyce. Sterne was the master of the marginal, the random, the inconsequential. In our own day, David Foster Wallace, Geoff Dyer and Ali Smith have become the paladins of this goofy manner. Like Dyer, who wrote an essay ostensibly about D.H. Lawrence, “Out of Sheer Rage,” and then turned it into a report on his own health, Smith seems obsessed with Lawrence as well.

In a story called “The Human Claim,” she juxtaposes an investigation into what happened to Lawrence’s ashes with a dispute she had with Barclaycard over unwarranted charges. The two themes don’t seem related — but that may be the point. Just as Dyer travels to Oaxaca to research Lawrence but ends up distracted by his own health problems, in the same way Smith’s speculations about who might have charged a Lufthansa flight on her credit card crowd out her questions about whether Lawrence’s widow’s new husband, tasked with cremating Lawrence’s corpse and bringing it back to New Mexico, may have dumped the cremains and substituted unrelated ashes in their place. Maybe that was the connection. “I began to wonder . . . who the person was, the person who’d pretended, somewhere else in the world, to be me. What did he or she look like?” If Lawrence’s ashes could be replaced with someone else’s and no one suspected the substitution for decades, maybe that could be related to contemporary identity theft.

This book, as the title suggests, is a homage to public libraries at a time when budget cuts in the United Kingdom (or the disunited Kingdom, now that Scotland and Ireland seem to be on the brink of seceding) and new ways of communicating are closing these free, life-changing institutions. Seeded throughout the text are brief testimonials by established writers, often from a humble and not especially literate background, for whom an early access to books made all the difference. Referring to the earlier British edition of the book, Smith notes that “by the time this book is published there will be one thousand fewer libraries in the U.K. than there were at the time I began writing the first of the stories.” Libraries are lauded because they too offer the randomness, the “serendipity” that characterizes Smith’s style. A woman starts out reading up on chemistry but keeps drifting back to the philosophy shelves — and soon has changed her major. Books in general are called “the best possible medium of the transmission of ideas, feelings and knowledge.” One letter writer even has a political take, that libraries are essential to a democracy so voters can be educated, “and that there is therefore an ideological war on them via cuts and closures.”

If the testimonials are part of a campaign to save libraries, the stories are more fanciful. Smith begins one with a gesture — a young poet throwing a Walter Scott novel on the floor only to notice when she picks it up that the binding is lined with sheet music. All of which allows the story to exfoliate into a host of subjects — the poet’s unhappy mother (she can hear her “shifting about upstairs like a piece of misery”), the poet’s witchiness, her prizes and eventually her confinement in a mental hospital. It ends: “Think of the Waverly collection on the shelves, the full 25 novels, their spines sliced back and open and the music inside them visible.” In Smith’s prose, the music inside is certainly visible.

Take this paragraph from the same story, when the poet is wondering if her badness is contagious: “Would it ruin the feel of the mouth of the hill pony on the palm of her hand when she went the hike by herself and gave it the apple she had for her lunch, the bluntness of the mouth, the breath of it, the whiskers round the mouth she could feel, the warm wet and the slaver on her hand that she wiped on her skirt and got into the trouble about?”

In the way of all successful art, Smith’s book triggered little chains of association that resonated with the other books I was reading at the time — the heart-stopping phrases in Rebecca West’s “The Fountain Overflows,” the wonderful tribute to the power of fiction to reconcile us to bright particulars in Martha Nussbaum’s “Love’s Knowledge,” that great homage to serendipity in Xavier de Maistre’s 18th-century “Voyage Around My Room.” As distinct and idiosyncratic as “Public Library” is, these intersections reveal how its themes are also timeless and universal.

In one of the first stories, the narrator is arguing with her father (who’s been dead for five years) about the past. He has seemingly perfect recall, remembers which prize she won for what, how she studied German years ago and how some German girls from Augsburg came over as exchange students; they had just learned about the Holocaust from a documentary and were speechless. The narrator, adrift in trivia, remembers that during World War I a man recorded all the various English and Irish dialects spoken by the soldiers (many of these dialects having since vanished). This idea of how people spoke in the past emphasizes how ephemeral both people and language can be. She thinks of her grandfather, who died before her birth: “I’ll never know what his voice sounded like.” She has a vision of a sort of huge golem that haunted her as a girl: “He speaks with all the gone voices.”

Books, libraries, writers, words — these are all Smith’s subjects. She tells us of the astonishingly common English words that were invented by John Milton. She tells us the original meaning of familiar words (“cheer” once meant “face”). She seldom fashions a good story in the usual sense; instead she gives us nosegays of associations, but these flowers have burrs. They stick in the imagination.

Unhappy romances (between women) are frequently the so-called back story. One woman wants to tell the other about her dream, but her partner doesn’t want to hear it. She accuses the narrator of playing stupid. There’s a lot about Dusty Springfield showing up in the unconscious.

These stories may be shattered or partial or half-buried, but the grateful reader does recognize that, unlike the more severely erased plots in some of Smith’s previous work, they contain the visible outlines of real and intriguing stories.

Edmund White’s most recent book is a novel, “Our Young Man.”